What is the social contract, and how does it apply to the international? We very briefly identify Thomas Hobbes and Woodrow Wilson, respectively, to define each. In the comparative and international contexts, early 20th century ethnographer Ruth Benedict offers important insights into the salience of cultural difference; those insights are amplified by French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas in his emphasis on absolute alterity. Benedict adopts and problematizes a schema to explain archetype-level (and macro-level) cultural differences between modern and traditional societies, including some traditional societies still existing in the West. In so doing, she draws upon Oswald Spengler and Friedrich Nietzsche. The result is that difference can be enormous and may be of profound importance. How should we reconcile that observation with coexistence in the international arena? We suggest that Wilson has offered us an international version of the social contract with some limits, highlighting a respect of difference and sovereignty at the domestic level as practiced within existing legal norms and responsibilities to the international sphere. That is, respecting the right of traditional peoples to their (lawful) traditional practices should be—and in some ways is—part of current conceptualizations of sovereignty at the domestic level. We imply a further emphasis on cultural sovereignty—a right to these (lawful) differences. It is suggested that greater attention is needed to coexistence with traditional and/or traditionalist peoples, cultures, economies, and social forces from the most remote contexts down to the metropole and within and across East, West, North, and South.

The International Social Contract

Thomas Hobbes outlines the basic need for order, and for what we now call social contract, sufficient to allow localized security so that individuals—children, elders, women, and men—can predictably go from home to work or school and back every day, even if work is in a nearby agricultural field. Indeed, Hobbes calls it the responsibility of the individual, by “general rule of reason,” to seek peace unless the other is refusing it (Hobbes 1997 (1651): 103-4). McLean (1981) identifies social contract with Hobbes and highlights its component of ceding individual liberty to a sovereign, warning of the need to consider, in some cases, self-defense against the sovereign. For Hobbes, what we now call the social contract—by which societies may guarantee, for example, safe agricultural fields, which produce food for a family, village or region, and overall personal security—is a necessity for human sustained existence as against perilous nature and criminal or similar forces (Hobbes 1997 (1651): 103, 129, 136-7, and 479 not adopting his valuation of cultures; see also 72, 82). The notion of an international social contract is related to philosophers of classical antiquity and the modern period from Protagoras and Cicero to Hobbes, Rousseau, and Kant by Thomas Weatherall. He, likewise, links the idea of an international social contract to notions of (agreed upon) peremptory laws and norms, international morality, moral reason, and human dignity, some of which have been incorporated into the Basic Laws of national states (Weatherall 2015: 67-8, 95-101).

Internationalist and progressivist Woodrow Wilson (Cude 2024: 26-7, 30, 55; a range of views, 123-4; against Lenin’s progressivism, 139-141) was not a strong advocate of the social contract, domestically speaking (Steigerwald 1994: 21-22). Nonetheless, his idea of internationalism and “cooperative politics” (Steigerwald 1994: 39) expanded a sort of notion of social contract applicable to the international arena, focusing on its core tenets to the relationships between states. Internationalism varied, some associating it with progress; others as a reaction against progressivism and fascism; some as an expression of national interest; others as a subordination of national interests (Steigerwald 1994: 42, 58, 135). The Wilsonian internationalism promoted a liberal political world, and, in philosophical terms, a form of idealism (Steigerwald 1994: 8, 135). Some scholars have suggested that, for Wilson, the concern with international cooperation and self-determination-under-most-circumstances were part of Wilson’s own conception of U.S. interests, that is, not a subordination of domestic interests; indeed, it was part of Wilson’s understanding of national security as rooted in a society not forced to become (internally, socially, and culturally) militarized due to international insecurity (Kennedy 2001: 10, 14, 21, 25).

At the height of World War I, the question emerged for he and many others (Trask 1983: 59, 61, 63, 67): why have world wars? What was the overall cause of them? By emphasizing the sovereignty of willing nation-states, he and others suggested that international organizations could ensure a common basis for the sovereignty (e.g., self-determination, initially to a limited list of participants defined by development status, Cude 2016: 157; regarding sovereignty, see Trask 1983: 62) and collective security of nations with the goal to “guarantee liberty and justice for frustrated or downtrodden peoples everywhere” (Trask 1983: 63). The League of Nations (to be replaced by the United Nations in 1945) was then established to provide a forum for international discourse on the issues of the day to promote peaceful coexistence and cooperation across nation-states and related authority systems.

Ruth Benedict: Coexistence, Conflict and Difference in Traditional and Modernist Archetypes

Ruth Benedict (2005 (1934)), on the other hand, tells us that Western modernism, by contrast to traditionalism (as found in the West and elsewhere), is characterized by at least three major philosophical, or even psycho-social-cultural, paradigmatic approaches. She draws these paradigms or archetypes from Oswald Spengler’s effort to identify or classify civilizational patters in The Decline of the West (2006 (English 1926, German 1918), as cited in Benedict 2005 (1934): 53), as well as from Friedrich Nietzsche’s typologies in The Birth of Tragedy (1910 (German 1872), as cited in Benedict 2005 (1934): 78). She impresses upon the reader that Western civilization cannot really be broken down into the civilizational patterns proposed by Nietzsche and Spengler, as there are more types today and additional manners in which one might interpret them (Benedict 2005 (1934): 54-5, 79, 85-8). Nonetheless, she draws upon them in her analysis of the Pueblo peoples. Moreover, her explanation in drawing together Spengler’s and Nietzsche’s typologies is an effective heuristic device for comparatively understanding differences between traditional and modernist approaches at an archetypal level.

In the terms of her day, she, like others, calls this traditionalism primitivism (Benedict 2005 (1934): 20, 50, 173). Early in Patterns of Culture, she indicates a cultural preference for white and Western cultures (Benedict 2005 (1934): 5-6, 13, 16), and the need not to engage in relativism in such regard. She discusses in detailed nuance the tension among Southwest Pueblo (e.g., Native American) cultures with relation to white North American cultures (22, 86, 92, 98, 118), accounting for Pueblo perspectives holistically and on their own terms. Similarly, she addresses the Trobriand and Dobu peoples (131, 144); and, briefly, cultural encounters and conflicts between white and African American (13), as well as a few additional contexts. She encourages comprehension of a “relativity” of cultures (11-12), seeking to account for valuation across practices more in social-theoretical and value-related than in schematic terms. For Benedict, some practices are good and others are bad.

On the other hand, her work expresses such a detailed knowledge of cultural variations in specific practices around the world—as well as a positive estimation and appreciation of the value of many of these—that it is hard to believe that the Western superiority outlined at the outset could be more than a cultural necessity of the era. Moreover, she addresses some communities that have historically engaged in practices such as cannibalism (e.g., valuatively negative or criminal in today’s terms). Thus, without taking evolutionary or patronizing approaches that appear in some parts of her book, it may be worth adopting some of her methods of arriving at such detailed knowledge. Her approach to the Faustian, Dionysian, and Apollonian worldviews might be summarized as follows.

For Benedict (drawing upon Spengler), some parts of Western society are playing with or negotiating various permutations and implications of the Faustian approach to the world. The Faustian archetype is based upon Goethe’s late-18th century work of poetic fiction, Faust (Goethe 1962 (1790)). The Faustian approach can be assumed to maintain a skeptic worldview as well as horror at the (violent) excesses of the modernizing world of the late 18th century. Nonetheless, for the Faustian archetype, “Conflict is the essence of existence” (Benedict 2005 (1934): 53); indeed, meaning itself is arrived at and experienced through conflict. The Faustian is concerned with the individual and its development, this latter arrived at primarily through conflict (Benedict 2005 (1934): 53-4). The traditional world, on the other hand, generally adopts an ancient Greek Apollonian approach. That approach includes respect for ritual, continuity, and tradition. According to Apollonian worldviews, we are all part of a greater universe of perfectly working parts, akin to a giant clock formed both artistically and scientifically. For the Apollonian, the notion of the individual will was somewhat foreign, as Benedict writes that “There was no place in his universe for will, and conflict was an evil which his philosophy decried” (53). (Perhaps the early years of the Abrahamic traditions in the West, with their focus on Divine love, sought or provided a softening of the Apollonian absence of individual will without, nonetheless, submitting to the Faustian bargain).

According to Benedict, Nietzsche separates the world of rituals in a different way: into the Dionysian and the Apollonian approaches (Benedict 2005 (1934): 79). The Dionysian seeks (intoxicant) excess and frenzy as means of achieving wisdom states. The Apollonian, through Benedict’s read of Nietzsche, distrusts intoxicant excess as means of arriving at wisdom (78-9); and he/she distrusts the skepticism (and (anachronistically applied) Nihilism?) of Faust. The Apollonian seeks the middle path (79) of the Apollonian Hellenic world, as Benedict defines it through Nietzsche. Early 20th century U.S. Southwest Pueblo culture among Native American communities is Apollonian in her analysis. Nonetheless, there is not a wholesale overlap between Greek and Pueblo cultures, Benedict emphasizes (79-80). It is only a central philosophical approach that is common between them at this archetypal or macro-level (Faustian vs. Apollonian vs. Dionysian).

Benedict notes as an interesting fact, overall, that some cultures cannot conceive of warfare (e.g., Eskimo cultures of Alaska), while for others it is central to their way of being (Benedict 2005 (1934): 31). These divides regarding questions such as conflict, in terms of cultural difference, may strongly separate some peoples in both domestic and international contexts. Then traditional cultures, can be generally said in Benedict’s terms, follow a middle way between Faust’s skepticism and horror at the world of late-18th century Europe (Scott has highlighted some of these in authoritarian high modernist examples, Scott 2020 (1998)), and Dionysus’ seeking of drugged or otherwise frenzied states for moments of enlightenment and wisdom. Traditional cultures, generally, are to be found in the Apollonian view for Benedict. That view roughly amounts to a generalized appreciation for the upholding of tradition and custom, and for moderation. There is variation in traditionalism, as some traditional communities may use intoxicants or even invoke inebriated states in certain ritual instances. There examples among the Southwest Pueblo peoples (Benedict 2005 (1934): 91), among Native American Peyote traditions (Benedict 2005 (1934): 89). In any case, one would not claim that all traditional societies are teetotaling.

Faust, on the other hand, may be anathema across the board for traditional cultures if Benedict is right in her estimation. Nonetheless, some traditional societies have experienced various types or degrees of what looks like authoritarianism from the outside, raising some obvious and not-so-obvious why questions regarding types, degrees of participatory governance, and (cultural) causes. These may include culturally- and socially-embraced emphases on various degrees of enforcement of non-conflict in the public sphere on certain issues in some societies, and the like—e.g., a public preservation of the peace for individuals from certain types of social conflict. In these ways, the Faustian and the Apollonian archetypes, in particular, may be strongly opposed.

Lévinas and the Absoluteness of Difference: Alterity

The implications of Benedict’s genius are significant. In relating Benedict, in these terms, to Hobbes’ social contract and Wilson’s international social contract, her insights include a recognition that we are very different, some of us from one another. We are not the same. Lévinas brings this point home in a way that is salient for the current discussion in his work, Alterity and Transcendence (Lévinas 1999 (1995)). For Lévinas, we have a propensity to view “…history as a harmonious process in which all problems are resolved, all conflicts settled, in which, in universality, all contradictions are reconciled” (Lévinas 1999 (1995): 85). We may, indeed, assume that conflict and difference are resolved and worked out through warfare. For Lévinas this approach is incorrect. He tells us that history is, rather, built upon various degrees of alterity and coexistence that may or may not be, ultimately, resolved (86-88). It is our relative willingness to recognize and appreciate the absolute alterity of difference (24, 88, 177, e.g., the other cannot be subsumed in the self, 11-12) without losing the self (e.g., the normal ego, the essential imperative of self-preservation, 97) that determines the extent to which we rise above such conflict in manners befitting the full recognition of human subjectivity required by Buber (Lévinas 1999: 98-101, see also 143; see also, comparing Buber, Lévinas, Said, and others, Sohn 2021). In so doing, we become fully human subjects ourselves, and we demonstrate our love of both neighbor and God (Lévinas 1999 (1995): 87-88, 95, 143). On the other hand, the other in full alterity calls to us in ways that invoke our inner spiritual and other human needs to concord and rapport (Lévinas 1999 (1995): 75, 98). For Lévinas, we must be cognizant of the need to self-preservation and not lose the self in responding to the other’s need to be met, or our own desire to meet the other (84, 94, 98-101, 131). From whatever our starting point may be (143), for Lévinas we do not want to be seduced by sanguine lies and related rhetoric about the other (177); neither do we want to be seduced by the other.

Conclusion

If we accept these insights of Benedict and of Lévinas, then we must accept and embrace the absolute difference of the other for what it is. If those differences remain within the realm of the lawful, then they are likely something to which we can adapt and which we can accept for the sake of coexistence and cooperation. If not, that is what international organizations are for: discourse on the hard issues of the day. Infighting on minor, mundane, and religious or profane—but lawful—practices and related epistemologies that may provide the foundations for cultural differences amongst us is not helpful in achieving Hobbes’ overall goal in the social contract: the sustaining of individual human life and communities over time. Squid Game (Dong-hyuk 2021-2025), or other methods of fighting out our differences in so many myriad Fight Club(s) (Fincher 1999) around the world, is a great solution for the expansion of criminality, the antithesis of Hobbes’ social contract.

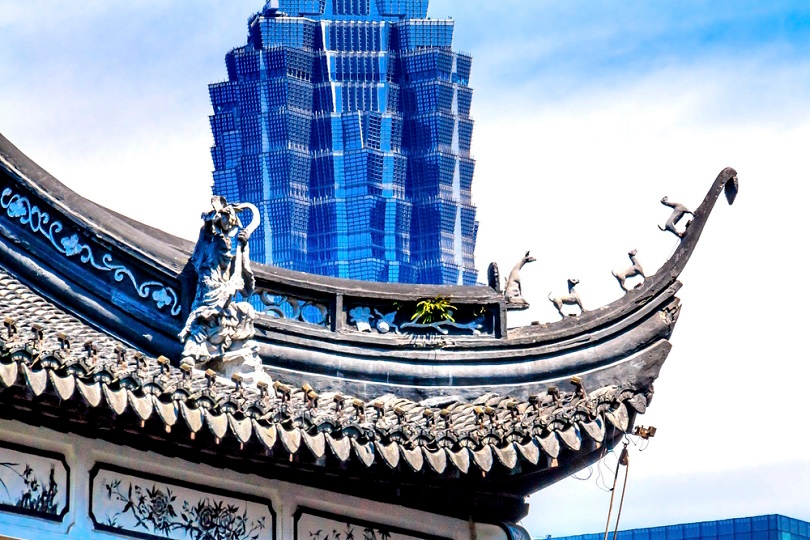

In domestic contexts worldwide (e.g., for example, the rural/urban divide; Sohn 2019) and in the international context, the acceptance of Hobbes’ domestic and Wilson’s international social contract, together with Benedict’s emphasis on difference and Lévinas’ absolute alterity, is more aptly achieved by allowing for: (a) traditional and modern economies to exist in tandem, domestically and internationally; (b) traditional livelihoods and cultures, including traditional industry and agriculture, small farms, nomadic communities, housewives who give their industry to their family endeavors, and the like; (c) new technologies; (d) lawful (in domestic and international terms) research, development, and science; (e) lawful (not relativist) cultural and religious freedoms and difference; and (f) modernist cities in which both traditional and modern cultures are embraced and welcomed. In providing this recommendation, the most remote contexts where people live traditional lives and thrive are considered—such as the Amazon basin, the Andes Mountains, the Arctic plain, the Asian Steppes, the Himalayan Mountains, the Masai Mara and Serengeti, and many desert areas of the world—as well as village and metropole (which may hold traditional and modern components in each).

The world remains both traditional and modern (in Nepal and South Asia, see Pyakurel 2026, 2024, 2022, 2021a, 2021b, 2007; Baral and Pyakurel 2015; see also Pyakurel and Sohn 2025; and as expressed in Asian popular film and television, Sohn 2025). Thinking about a world map in which the vast majority of people live in Asia, Africa, and South America (see, “Current World Population”), and in which rural/urban and traditional/modern divides still persist in North America and Europe as well (see, for example, Cramer 2022 (2016), and Weyrauch 2001), the fact of coexisting traditionalism and modernism is apparent. That coexistence may be tense and conflict-ridden, or peaceful and collaborative, depending upon context and our own choices. The suggestion herein is that it need not always be driven by conflict or averse relations. Social contract at the domestic and international levels should include both dimensions—traditional and modern—in order, ultimately, to achieve Hobbes’ goal of security at the individual and community levels, wherein, by a logic of internationalism, the individual is any given human person at any given moment at any location in the world.

REFERENCES

Baral, Lok Raj and Uddhab P. Pyakurel. 2015. Nepal – India Open Borders: Problems and Prospects. Delhi: Vij Books India Pvt. Ltd.

Benedict, Ruth. 2005 (1934). Patterns of Culture. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Cramer, Katherine J. 2022 (2016). The Politics of Resentment: Rural Consciousness in Wisconsin and the Rise of Scott Walker. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cude, Michael. 2024. Woodrow Wilson: The First World War and Modern Internationalism. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

Cude, Michael R. 2016. “Wilsonian National Self-determination and the Slovak Question during the Founding of Czechoslovakia, 1918-1921” in Diplomatic History 40 (1): 155-180.

“Current World Population.” 2025. World Population Clock, https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/ (accessed November 25, 2025).

Dong-hyuk, Hwang, dir. 2021–2025. Squid Game. ((TV-MA), Korean, English, and Urdu with English Subtitles). Seoul: Firstman Studio. Los Angeles: Siren Productions.

Fincher, David, dir. 1999. Fight Club. ((R), English). Century City, CA: Fox 2000 Pictures, et al.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. 1962 (1790). Faust. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

“History of the United Nations.” United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/history-of-the-un (accessed November 25, 2025).

Hobbes, Thomas. 1997 (1651). The Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasicall and Civil. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Hsu, Francis L. K. 1973. “Prejudice and Its Intellectual Effect in American Anthropology: An Ethnographic Report” in American Anthropologist 75 (1): 1-19.

Kennedy, Ross A. 2001. “Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and an American Conception of National Security” in Diplomatic History 25 (1): 1-31.

Lévinas, Emmanuel. 1999 (1995). Alterity and Transcendence. New York: Columbia University Press.

McLean, Ian. 1981. “The Social Contract in Leviathan and the Prisoner’s Dilemma Supergame” in 29 (3): 339–51.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1910 (German 1872). The Birth of Tragedy, or Hellenism and Pessimism. In The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Volume One, edited by Oscar Levy. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. New York: Macmillan Company.

Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. 2013. “What is Global Studies?” in Globalizations 10 (4): 499–514.

“Predecessor: The League of Nations.” United Nations, https://www.un.org/en/about-us/history-of-the-un/predecessor (accessed November 25, 2025).

Pyakurel, Uddhab. 2026. “State of Women in Nepal’s Politics” in Women’s Reservation and Politics: Past, Present and Future, edited by Mayanglambam Lilee. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company Pvt. Ltd.

Pyakurel, Uddhab. 2024. “Urban Youth Perspectives / Urban Youngsters’ Perspectives on Family, Work and Society in the Future: A Study of Social Science Students in Kathmandu, Nepal” in Political Science Journal 2 (1): 69-82.

Pyakurel, Uddhab. 2022. “Inner-party Democracy in Nepal” in Rooting Nepal’s Democratic Spirit, edited by Amit Gautam. Kathmandu: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

Pyakurel, Uddhab.2021a. Reproduction of Inequality and Social Exclusion: A Study of Dalits in a Caste Society, Nepal. Singapore: Springer Nature.

Pyakurel, U. P. 2021b. “A Quarter Millennium of Nepal’s Foreign Policy: Continuity and Changes” in The SAGE Handbook of Asian Foreign Policy, Volume 2, edited by Takashi Inoguchi. London; Thousand Oaks, CA; and New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Pyakurel, Uddhab P. 2007. Maoist Movement in Nepal: A Sociological Perspective. New Delhi: Adriot Publishers.

Pyakurel, Uddhab and Patricia Sohn. 2025. “Kathmandu: City of Peace, Economies of Scale and Cultural Diversity” in E-International Relations. October 29, 2025.

Scott, James C. 2020 (1998). Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sohn, Patricia J. 2025. “Asian Perspectives and Ritual Politics in Recent Popular Film and Television” in Religions 16 (11): 1449 (35 pages).

Sohn, Patricia. 2021. “Theatres of Difference: The Film ‘Hair’, Otherness, Alterity, Subjectivity and Lessons for Identity Politics” in E-International Relations. September 28.

Sohn, Patricia. 2019. “J’accuse! The Case for Pre-modernism, or, the Rural-urban Divide” in E-International Relations. January 25.

Spengler, Oswald. 2006 (English 1926, German 1918). The Decline of the West. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Steigerwald, David. 1994. Wilsonian Idealism in America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Trask, David F. 1983. “Woodrow Wilson and International Statecraft: A Modern Assessment” in Naval War College Review 36 (2): 57-68.

Weatherall, Thomas. 2015. Jus Cogens: International Law and Social Contract. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Weyrauch, Walter O. 2001. Gypsy Law: Romani Legal Traditions and Culture. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA, and London: University of California Press.

Further Reading on E-International Relations